Pierre-Benoit Joly, INRA/TSV

Alain Kaufmann, University of Lausanne

Download Presentation [610 kb, ppt]

The context

Drawbacks of the “Public Understanding of Science” or “deficit model” are now widely acknowledged

The PUS programme was launched in 1985 by the British Royal Society. It was based on the idea that lay citizens’ resistance to innovation is related to a lack of knowledge and that “the public” has to be educated and informed in order to secure support for innovation and reduce social resistance to technology.

Further analysis have shown that the assumption on which this programme was based is not valid. Such a linear relation between knowledge and technophily does not exist. At the contrary, resistance to technological change is more important in high education societies –these societies correspond more to what Beck calls “risk societies”. Technocritics are not at all ignorant; they generally have quite a high level of education.

The problem is that institutions generally still believe in the “deficit model”. They misunderstand public’s so-called misunderstanding of sciences as shown by Brian Wynne, from the University of Lancaster.

Hence, a communication strategy based on the deficit model may yield negative results.

In the case of GM food, such communication was often contradictory as illustrated on this slide, « This being new apple! Better! More miam miam! No danger! You understanding me? »

It explained at the same time that GM is a technological breakthrough but that it does not present any risks. Such a contradictory discourse has fed a sense of distrust of scientific institutions.

“Deliberative or participatory turn”

- Democratic deficit in S & T

- Environmental crisis and other controversies; learning from the GMO controversy

- Questioning experts and decision makers in risk assessment and management

- Activists or concerned groups (“scientific citizenship”)

Against the “deficit model” some European institutions have developed participative initiatives. The basic idea is that it is necessary to shift from technological acceptance to upstream engagement. Upstream participation, it is claimed, should allow increase trust in institutions through open discussion on technological regulation and it should allow to better adapt technological innovation to societal’s needs.

Technology Assessment (TA, pTA, CTA, RTTA,…) as a way out

Hence, since the mid 80’s a set of methodologies (technology assessment, participative technology assessment, constructive technology assessment, real time technology assessment,…) have been designed and used.

Varieties of public engagement

- Rowe and Frewer (2000; 2005): have identified up to 100 different mechanisms, from one-way communication to mechanisms which are characterised by a process of empowerment of participants.

- Public communication, PUS or public instruction model (Callon): TV broadcast, hotline, conferences, etc.

- Public consultation: referenda, surveys, focus groups, etc.

- Public participation, public debate model (Callon): citizens’ juries, citizens’ and consensus conferences, planning cells, etc.

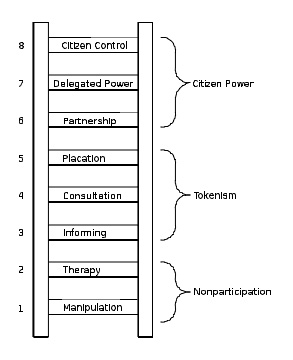

Eight rungs on the ladder of citizen participation

This variety of mechanisms was already identified by Sherry Arnstein some 40 years ago. The ladder of citizen participation thus included a wide range of mechanisms, from communication/propaganda to delegation of the power to those who are affected by the decision at stake.

A Ladder of Citizen Participation - Sherry R Arnstein, Originally published as Arnstein, Sherry R. "A Ladder of Citizen Participation," JAIP, Vol. 35, No. 4, July 1969, pp. 216-224.

A definition

In order not to get confused with a range of heterogeneous mechanisms, we propose to stick to quite a narrow definition:

“Public participation” encompasses a group of procedures designed to consult, involve, and inform the public to allow those affected by a decision to have an input into that decision.”

Public participation is subject to various criticism, including from being a type of populism. Why consult lay citizens who have neither the scientific competence nor the political legitimacy?

This cartoon published during the 2007 French political elections (Ségolène Royal, candidate for the Socialist Party organised many participative debates to build her political project). It illustrates just one of the many nasty reactions provoked by public participation initiatives. « S.R: Your ideas are mine. Man: I thought she was more intelligent »

So the first point is to consider the potential benefits of public participation

Benefits expected from public participation in science and technology

Quality of knowledge (epistemic argument): lay people and stakeholders can contribute to knowledge production and identify solutions which can improve the innovation process; limited rationality; e.g. lay epidemiology

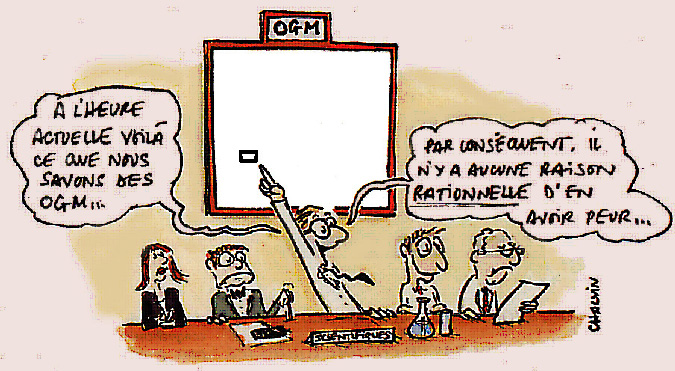

« Currently, here is what we know about GMOs… Thus there is no rational reason to be frightened! »

Also, public deliberation on scientific issues may help open some black boxes:

- discuss implicit value judgements which are entangled in technological choices

- discuss implicit hypothesis or inferences made to overcome lack of knowledge on possible impacts or dangers

Democratic deficit (normative argument): participation improves democracy and enhances citizenship; deliberative democracy, empowerment

The second argument in favour of public participation is more normative. Since it enhances citizenship, participation improves democracy. Active concerned groups who participate in the building of a collective decision perform a political work in the sense that they compose to define locally what is the common good.

This is related to the idea of deliberative democracy and to habermasian ideas of ethics of discussion. This may raise problems in countries like France which are characterised by a strong technocratic tradition. However, even in this case, we observe a strong move tpwards the generalisation of rights to be informed and rights to participate (Cf. Convention of Aarhus in the case of projects which affect the environment)

Political legitimacy (instrumental argument): participation allows a more inclusive governance in a context characterised by a growing complexity and by a loss of public interest in politics; re-inforces legitimacy

Finally, there is also an instrumental argument: in complex situations where knowledge is distributed, action may involve collective learning. Thus participation may improve the design and the implementation of a given projet.

A short glance at pTA experiences

To make brief a long story, we can first refer to the many experiences of public participation in science and technology organised so far, mainly in Europe.

The starting point of the deliberative turn is in Danemark, where « consensus conferences » have been invented. To be fair, consensus conferences already existed in medicine. In many countries, this exists as a form of deliberation between experts in order to find a consensus on the best way to deal with a pathology (osteoporose, post-coma therapeutics, etc.). Such deliberations are interdisciplinary and are directed towards experts’ consensus.

In 1985, the Danish Board of Technology proposed to adapt consensus conferences. The key invention was to put a panel of lay citizens at the core of the consensus conference. This makes a tremendous difference.

This new model of consensus conference has had an impressive fate.

List of consensus conferences organised in Denmark (1987-2002)

It is often used in Danemark. And thus far, it has been used on quite different issues.

- Testing our Genes (2002)

- Roadpricing (2001)

- Electronic Surveillance (2000)

- Noise and Technology (2000)

- Genetically modified Food (1999)

- Teleworking (1997)

- The Consumption and Environment of the future (1996)

- The Future of Fishing (1996)

- Gene Therapy (1995)

- Where is the Limit? – chemical substances in food and the environment (1995)

- Information Technology in Transportation (1994)

- A Light-green Agricultural Sector (1994)

- Electronic Identity Cards (1994)

- Infertility (1993)

- The Future of Private Automobiles (1993)

- Technological Animals (1992)

- Educational Technology (1991)

- Air Pollution (1990)

- Food Irradiation (1989)

- Human Genome Mapping (1989)

- The Citizen and dangerous Production (1988)

- Gene Technology in Industry and Agriculture (1987)

List of consensus conferences organised elsewhere :

Also, as shown below, the model of consensus conferences is the most widespread mechanism of public participation.

This list is not comprehensive, but it gives a good overview of the type of countries and type of subjects. In some countries, the model has been adapted to national context. For instance, in Switzerland, it was renamed « Publiforum »; in France « Conférence de citoyens » (because France has a problem with the idea of consensus).

- ARGENTINA Genetically modified foods (2000); human genome project (2001).

- AUSTRALIA Gene technology in the food chain (1999)

- AUSTRIA Ozone in the upper atmosphere (1997)

- CANADA food biotechnology (Western Canada, 1999); municipal waste management (Hamilton City/Region, 2000)

- FRANCE Genetically modified foods (1998), Climate Change (2001), Domestic wastes (2004), Public transportation in South East (2006), Nanotechnology (2007)

- GERMANY Citizens' Conference on Genetic Testing, (2001 Deutsches Hygiene-Museum)

- ITALY Consensus Conference on GMO’s

- ISRAEL Future of transportation (2000)

- JAPAN Gene therapy (1998); high information society (1999); genetically modified food (2000)

- NETHERLANDS Genetically modified animals (1993); human genetics research (1995)

- NEW ZEALANDS Plant biotechnology (1996); plant biotechnology 2 (May 1999); biotechnological pest control (Sept. 1999)

- NORWAY Genetically modified foods (1996); smart-house technology for nursing homes (2000)

- SOUTH KOREA Safety & ethics of genetically modified foods (1998); cloning(Sept. 1999)

- SWITZERLAND National electricity policy (1998--conducted in 3 languages with simultaneous translation); genetic engineering and food (June 1999); transplantation medicine (Nov. 2000)

- U.K. Genetically modified foods (1994); radioactive waste management (May 1999)

- U.S.A.: Telecommunication technologies (1999), Nanotechnology (2005)

Tool box for civil society participation

However, to some extent, Consensus Conferences are the tree which hides the forest.

Actually as shown below, there are quite a few participation mechanisms.

- Advisory committees

- Citizen’s advisory councils

- Citizen’s jury (including planning cells, etc.)

- Consensus conference

- Focus groups

- Future Workshops

- Mediation

- Negotiated rule making

- Planning for real

- Public hearings

- Public survey

- Referendum

- Scenario Workshops

- ...

(Ifok, For the European Conference on Civil Society Participation, June 2003)

These mechanisms rank very differently on Arnstein’s ladder of public participation.

Also, such mechanisms may be used in combination and/or adapted to the context.

For instance, GM Nations! organised in 2003 in the UK was based on combination of focus groups, inclusive public debates and electronic consultation. It involved up to 20 000 people.

Thus, public participation is not a single ready-to-use tool.

It is a specific approach for the governance of science and technology. This approach is based on general principles and implemented through a set of mechanisms.

Public participation has to be tailored to each case, according to the type of socio-technological issue at stake. Such adaptation may benefit from knowledge and competencies accumulated in past experiences and has to carefully take into account the general principles.

Potential drawbacks

Indeed, since more than 20 years, many experiences have taken place: quite a few participation mechanisms have been designed and implemented. However, participation is not yet and easy matter. And any single project is confronted to questions and difficulties.

Some « hot issues » concerning participation

- What is the political legitimacy of PP ?

How does this articulate with other types of legitimacies (political representation, scientific competence, NGOs engagement,…) - How are PP connected to political decision ?

Is it just about legitimising already taken decisions? / What is the commitment of the initiator? Will she actually take into account the outcomes of PP? - Which impact for PP on the public sphere, science and technology policy, and innovation processes ?

It is important to consider the various dimensions of possible impact and to address them thoroughly.

We may have different reasons to initiate public participation; the clarification of the goal and expected impact is instrumental - Which method to choose, for which objective and in which context ?

There is not one single way to design and organise public participation

Indeed, the choice of method is also important.

Providing knowledge and information on these questions is one of the key objectives of this training workshop. Indeed, it would be contradictory to preach for participation while sticking on one-way mode of communication. So, it is time for you to have the voice.

Metaplan presentation

So, the next step is to have a Metaplan in order to discuss your expectation on this training workshop. (Metaplan is a registered trademark. Copyright is held by Thomas Schnelle GmbH, please see www.metaplan.com)

Metaplan exercise:

- Articulation of individual analysis and group discussion

- Collective elaboration (framing) of an issue

The question you are going to work on:

“ What do I want to learn about citizen participation in science and technology ? ”

Guidelines:

- Group discussion (split in groups of 5 to 12 people/ form a circle where everyone sees everyone / one facilitator for each group)

- Each participant has 5 « Post-it » Notes to answer the question. Answers thus have to be quite short and written in capital letters

- Participants spend about 10 min without discussion to think of and write their answers

- Facilitator collects the notes 1/1: the start is by hazard and then participants are invited to give their notes if they think it is the same theme as the previous one.Then a new theme is started (and so on)

- Facilitator may help participants rephrase their answers when needed. He sticks the notes on a big paperboard, and thus forms clusters. The facilitator also helps participants to name the clusters

- At the end of the Metaplan (which lasts about 1 hour) each group has produced a set of clusters (name of the cluster + items). If they are several groups, they may share their results. The trainer then has to explain how the questions raised in the Metaplan will be addressed throughout the workshop.